图尔明模式及其应用研究

ChapterOneIntroduction1ChapterOneIntroductionAstheglobalizationoftheworldaccelerates,thetaskofteachingEnglish(consideredtobeaninternationallanguage)becomesmoreandmorecommanding.Althoughsomeprogresshasbeenmade,itseemsthatwestillhavealongwaytogo.AmongthefivebasicskillsofEnglish(listening,speaking,read...

相关推荐

-

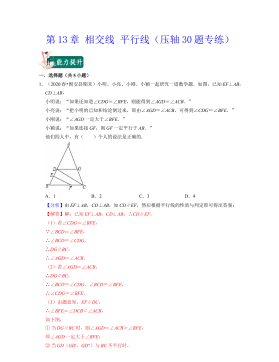

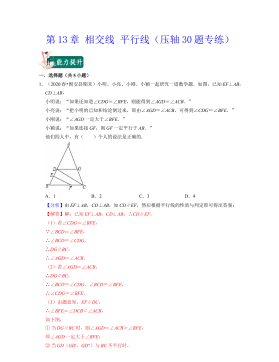

七年级数学下册(易错30题专练)(沪教版)-第13章 相交线 平行线(原卷版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 25

2024-10-14 25 -

七年级数学下册(易错30题专练)(沪教版)-第13章 相交线 平行线(解析版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 28

2024-10-14 28 -

七年级数学下册(易错30题专练)(沪教版)-第12章 实数(原卷版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 27

2024-10-14 27 -

七年级数学下册(易错30题专练)(沪教版)-第12章 实数(解析版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 19

2024-10-14 19 -

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第15章平面直角坐标系(原卷版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 19

2024-10-14 19 -

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第15章平面直角坐标系(解析版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 27

2024-10-14 27 -

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第14章三角形(原卷版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 19

2024-10-14 19 -

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第14章三角形(解析版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 30

2024-10-14 30 -

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第13章 相交线 平行线(原卷版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 26

2024-10-14 26 -

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第13章 相交线 平行线(解析版)VIP免费

2024-10-14 22

2024-10-14 22

作者详情

相关内容

-

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第15章平面直角坐标系(解析版)

分类:中小学教育资料

时间:2024-10-14

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:15 积分

-

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第14章三角形(原卷版)

分类:中小学教育资料

时间:2024-10-14

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:15 积分

-

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第14章三角形(解析版)

分类:中小学教育资料

时间:2024-10-14

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:15 积分

-

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第13章 相交线 平行线(原卷版)

分类:中小学教育资料

时间:2024-10-14

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:15 积分

-

七年级数学下册(压轴30题专练)(沪教版)-第13章 相交线 平行线(解析版)

分类:中小学教育资料

时间:2024-10-14

标签:无

格式:DOCX

价格:15 积分